By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

|

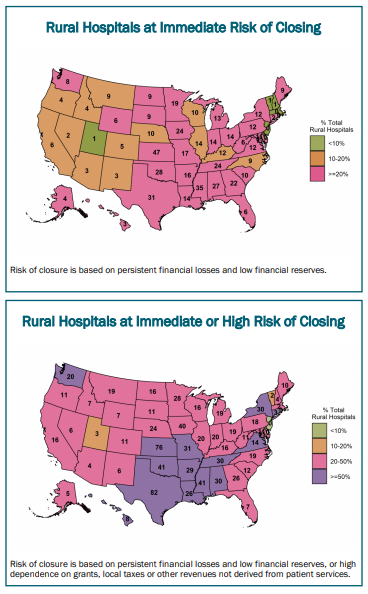

| Maps from "Rural Hospitals at Risk of Closing" report |

Harold Miller, president and CEO of the center, told Kentucky Health News that the report doesn't name the hospitals the center considers at risk because it's hard to say exactly what is going on in each of them without digging a bit deeper into their individual stories, and he doesn't want to imply that the only hospitals struggling are the ones he puts on a list.

"This was more intended to say to the state, 'Guess what, you have a bunch of hospitals that are not doing well and you shouldn't ignore that problem'," he said.

The "Rural Hospitals at Risk of Closing" report says that of the 69 hospitals in Kentucky that it considers rural, 16, or 23%, are at risk of closing. Among those, 12 are at immediate risk of closing and four are at a high risk of closing, it says.

The report says hospitals with an immediate risk of closing have had persistent financial losses, meaning "the hospitals had a cumulative negative total margin over the most recent three-year period for which financial data were available" and had a low or non-existent financial reserve, meaning the hospitals either "had total liabilities exceeding all assets other than buildings or equipment or had assets greater than liabilities, but only by enough to sustain continued losses for at most two years."

At first glance, one hospital that seems to fit those criteria is what is now called the Ephraim McDowell James B. Haggin Hospital in Harrodsburg.

The report shows this hospital lost $863,095 in 2017-19, a margin of minus 3.7%. But just as Miller cautioned, there is often more to a hospital's story than just the numbers.

William Snapp, executive vice-president and chief financial officer of Danville-based Ephraim McDowell Health told Kentucky Health News that when this hospital became part of the McDowell system in 2017 it was losing money, but since becoming part of McDowell's centralized system, along with some changes in how it operates, it now has a positive margin and is at no risk of closing.

"We have no intention of closing James B. Haggin," Snapp said. Later adding, "The synergy of all of these together as a system is quite effective, and so that makes Haggin a very valuable asset to the system as a whole."

Kentucky Health News unsuccessfully sought comment from two other hospitals with similar figures in the report, the Kentucky River Medical Center in Jackson and AdventHealth Manchester.

The report says the Jackson hospital lost an average of $1.6 million a year in 2017-19, an operating margin of minus 5.2%. The hospital did not respond to a request for comment.

The Manchester hospital, part of a nine-state chain based in Florida, showed a minus 4.1% margin in 2017-19, representing a loss of $2.4 million. The hospital's marketing manager, said its CEO was traveling and would return the call, but the CEO had not by Sunday night.

The report says the primary cause of rural hospital closures is that payments from government and private health-insurance plans is less than the cost of delivering care to patients in rural communities; that these payments are not enough to sustain their essential services.

Rural hospitals' financial troubles are often blamed on low reimbursement from Medicare and Medicaid, but Miller said some small rural hospitals have more trouble with private health plans, which pay them less than big hospitals for the same care, and less than the cost of delivering that care.

"It's not as if there is just one thing that explains why they're losing money," Miller said. "In some cases, it's more Medicaid patients, in some cases, it's bad payments by commercial payers. In some cases, and it's hard to tell that from these data, it's sometimes the mix of services that hospital offers."

The report shows the payer mix of hospitals and what they make or lose on patient services in addition to their total margins. It reviews many of the problems faced by rural hospitals and analyzes many of the proposed solutions, and offers a new approach.

It proposes a two-part payment model that would require an up-front payment from both public and private insurers based on the number of plan members who live in the community, regardless of the number of services provided, along with a service-based fee much lower than current payment models.

This "patient-centered payment system" would ensure "that the hospital has adequate revenues to support the minimum standby costs of essential services, such as the emergency department, inpatient unit and laboratory," and the service fee "would ensure that if patients need more services, the hospital would receive sufficient additional revenue to cover the added costs of delivering those services, rather than being forced to delay or ration care," the report says.

"We need to do something different," said Miller. "All the stuff we've tried so far hasn't worked."

What's Kentucky doing to help?

Kentucky lawmakers passed a bill last year to help rural hospitals, but didn't fund it. This year, they are working to pass one that would increase Medicaid funding for many of them.

In the 2020 legislative session, the General Assembly passed House Bill 387 to create a revolving loan fund for distressed rural hospitals, but didn't fund it. If funded, it would allow the state Cabinet for Economic Development to make loans to struggling hospitals for three things: maintain or upgrade facilities; maintain or increase staff; or to provide health services not currently available. The loans could run 20 years and would be available to hospitals in counties with fewer than 50,000 people.

This year, Rep. Brandon Reed, R-Hodgenville, has filed House Bill 183, which would allow Kentucky hospitals to get more money from Medicaid, at an "average commercial rate" instead of the current Medicaid rate, which is often below that amount. The program would not cost the state anything because Kentucky's hospitals have agreed to cover the cost. And to receive the funds, hospitals will have to abide by higher quality standards that are still being decided by the Kentucky Hospital Association and the Cabinet for Health and Family Services. The House passed the bill and sent it to the Senate on a 93-0 vote Feb. 11.

Reed told the House that Kentucky hospitals have encountered additional financial challenges during the pandemic and are facing $2.6 billion in losses because of it.

This "patient-centered payment system" would ensure "that the hospital has adequate revenues to support the minimum standby costs of essential services, such as the emergency department, inpatient unit and laboratory," and the service fee "would ensure that if patients need more services, the hospital would receive sufficient additional revenue to cover the added costs of delivering those services, rather than being forced to delay or ration care," the report says.

"We need to do something different," said Miller. "All the stuff we've tried so far hasn't worked."

What's Kentucky doing to help?

Kentucky lawmakers passed a bill last year to help rural hospitals, but didn't fund it. This year, they are working to pass one that would increase Medicaid funding for many of them.

In the 2020 legislative session, the General Assembly passed House Bill 387 to create a revolving loan fund for distressed rural hospitals, but didn't fund it. If funded, it would allow the state Cabinet for Economic Development to make loans to struggling hospitals for three things: maintain or upgrade facilities; maintain or increase staff; or to provide health services not currently available. The loans could run 20 years and would be available to hospitals in counties with fewer than 50,000 people.

This year, Rep. Brandon Reed, R-Hodgenville, has filed House Bill 183, which would allow Kentucky hospitals to get more money from Medicaid, at an "average commercial rate" instead of the current Medicaid rate, which is often below that amount. The program would not cost the state anything because Kentucky's hospitals have agreed to cover the cost. And to receive the funds, hospitals will have to abide by higher quality standards that are still being decided by the Kentucky Hospital Association and the Cabinet for Health and Family Services. The House passed the bill and sent it to the Senate on a 93-0 vote Feb. 11.

Reed told the House that Kentucky hospitals have encountered additional financial challenges during the pandemic and are facing $2.6 billion in losses because of it.

That number comes from a KHA report, which says, "Many rural hospitals were in dire financial shape prior to the pandemic and are at risk of closing. The additional stress of Covid-19 puts them at further risk, threatening access to needed care in several Kentucky communities."

Five hospitals have closed in Kentucky since 2009, four since 2014. The most recent was Our Lady of Bellefonte Hospital in Russell, which closed in April.

The center's report includes data on the size and financial status of each hospital, their margin trends for the past three years in most cases, their payer mix and margins, the sources of their profits and losses, and their assets available to cover their losses.

The data was obtained from cost reports that hospitals are required to submit each year to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Data was only included if the report covered a full fiscal year and provided operating expenses, according to the report's methodology page.

|

| Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform table includes Kentucky hospitals that averaged a three-year loss. Click here for all the data. The other column to pay attention to is "Total net assets." |

No comments:

Post a Comment