UPDATE, March 1: The House sent the bill to the Senate on 94-4 vote.

UPDATE, March 16: The Senate Health & Welfare Committee passed the bill with a committee substitute.

By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

A bill to require Medicaid reimbursement for certain services provided by certified community health workers, and streamline their certification process, awaits a vote in the full House.

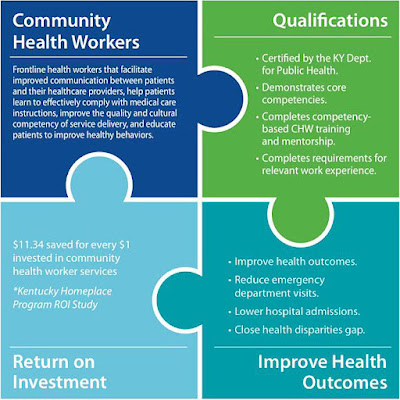

CHWs aren't trained medically, but are trained as patient advocates who come from the communities they serve. They help their clients coordinate care, provide access to medical, social and environmental services, work to improve health literacy and deliver education on prevention and disease self-management.

|

| Rep. Kim Moser at a Feb. 17 briefing on HB 525 (News release photo) |

The federal Bureau of Labor Statistics says Kentucky had 1,350 CHWs in May 2020, with an annual average wage of $37,320.

House Bill 525, sponsored by Moser, would require the Department for Medicaid Services to seek federal approval for a state plan amendment, waiver or alternative payment model, including public-private partnerships, for services delivered by certified CHWs.

The bill would also require CHWs to be employed and supervised by a Medicaid-participating provider and says as of Jan. 1, 2023, "no person shall represent himself or herself as a community health worker unless he or she is certified as such" in accordance with the provisions laid out in the act.

The bill passed out of the House Health and Family Services Committee, which Moser chairs, on Feb. 24. She pointed to a Kentucky Homeplace study that found between July 2001 and June 2021, community health workers achieved a return on investment of $11.32 saved for every $1 invested in their services.

"The cost-benefit analysis has shown it to be a very productive use of our taxpayer dollars," she said, adding that because Kentucky expanded Medicaid under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2014, the program serves 1.6 million Kentuckians, about one of every three.

"We know that it's time, because of this Medicaid expansion, to really get more targeted with our Medicaid dollars and work on programs that work," Moser said.

Emily Beauregard, director of Kentucky Voices for Health, said Moser's bill, if passed, could be a "real game-changer" toward providing a sustainable funding source for community health workers in Kentucky.

"House Bill 525 creates a very, very important pathway to expand our current network of community health workers," Beauregard said.

Pamela L. Spradling, a CHW with Big Sandy Health Care, a federally qualified health center in Prestonsburg that covers five counties, said their CHWs are currently paid as staff or through grant funding.

"I am proud to say our transportation service has provided just shy of 1,300 rides to our most vulnerable population in 2021," she said in a statement prepared for the House committee. "The team consists of one full-time driver, one part-time driver who was recently hired, two outreach and enrollment specialists, and three community health workers ready to assist our patients when needed."

"It is our hope that payers will recognize the benefit of CHWs and consider coverage for their services," Collett said.

No comments:

Post a Comment