Kentucky Health News

Federal pandemic money helped to shore up rural hospitals as they worked to care for increased volumes of critically ill patients, but many of them were at risk of closure before Covid-19 hit, and the financial challenges creating that risk have not gone away.

"Rural hospitals that were struggling before the pandemic will once again be at risk of closure unless additional action is taken to shore up these facilities," says a new report from the Bipartisan Policy Center.

In 2020, a report from the Kentucky Hospital Association said "anywhere from 16 to 28" of the state's 68 rural hospitals were at risk of closing. An analysis in 2021 by the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform found that 16 of the 69 Kentucky hospitals it considered rural were at risk of closing.

Five hospitals have closed in Kentucky since 2009, four since 2014. The most recent was Our Lady of Bellefonte Hospital in Russell. It closed in April 2020, but has since been purchased in part by Addiction Recovery Care, which plans to make it a comprehensive center for treating substance-use disorder.

The BPC report, The Impact of COVID-19 on the Rural Health Care Landscape, examined the ongoing financial and personnel challenges facing rural hospitals through the lens of eight states: Iowa, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, North Dakota, South Dakota and Wyoming.

It lays out short- and long-term policy recommendations to strengthen rural care, and to serve as a bridge as health-care systems exit the pandemic.

It says that during the pandemic, the pace of rural hospital closures slowed, due mainly to the pandemic-relief money they received: "In 2021, only two hospitals closed, down from 19 in 2020, marking a significant reduction from the 138 closures between 2010 and 2020."

George Pink, deputy director of the North Carolina Rural Health Research Program at the University of North Carolina, said in a June 29 webinar that the federal help came largely from the relief funds allocated for providers and the broader Paycheck Protection Program.

"The estimated distribution of provided relief funds to rural hospitals was almost $15 billion as of February 21," said Pink. "And this funding really allowed many hospitals to survive during the pandemic, and probably prevented many rural hospitals from closing."

Other key stabilizers for rural hospitals were a temporary moratorium on "sequestration reductions," the scheduled 2 percent payment reductions for Medicare services, and the enhanced payments provided by Congress for telehealth services rendered during the pandemic.

The concern is that as these measures end and personnel shortages persist, rural hospitals that struggled before the public health crisis will find themselves in dire financial straits again.

Pink ticked off a list of challenges rural hospitals face. First, they serve small populations that are typically older, sicker, under-insured or uninsured. Also, they have low patient numbers that don't create enough revenue to cover the fixed cost of a 24-hour emergency department; high percentages of patients on Medicare, programs that often don't cover the cost of care; and struggles with recruiting health-care providers.

With the last pandemic funds soon to be distributed, Pink said he expects rural hospitals to fall to pre-pandemic levels of profitability. "In fact, profitability can decline even faster because of what hospitals are now having to pay for labor, particularly nursing," he said.

|

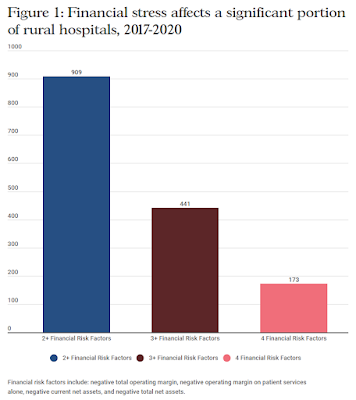

| Bipartisan Policy Center graphic; for a larger version, click on it. |

The BPC also assessed the financial vulnerability of 2,176 rural hospitals between 2017 and 2020. IT found that 909 had two or more concurrent financial risk factors that put them at risk of service reduction or closure; 441 of them faced three or more risk factors; and 173 of them had four or more. The factors included negative operating margins (total and on patient services alone), negative current net assets, and negative total net assets.

Asked if their hospitals would survive without the federal relief money, Joan Hall, president of Nevada Rural Hospital Partners, a consortium of Nevada's 13 critical-access hospitals, said the hope is that there will be more money coming, but they are not sure there will be.

"I think that is a something we're very worried about," said Hall. "We're seeing still sicker patients, patients with different kinds of of needs that typically we've not had to provide care for in rural areas."

And just last week, she said, Nevada had 600 hospital patients who couldn't be transferred to long-term care and skilled nursing facilities because those facilities can't accept new patients, and that "clogs up the pipeline for rural patients who need a higher level of care."

Joe Schindler, vice president of finance, policy and analytics at the Minnesota Hospital Association, added that it would be "disastrous" for hospitals that have depended on money from programs like the Medicare Dependent Hospital Program, which helps smaller hospitals that are heavily dependent on Medicare patients and is set to expire on Sept. 30, to lose this funding.

"This is the worst time probably to pull the rug out on programs that have helped support rural access for many of those hospitals that need those supports," he said.

When rural hospitals close, it creates obstacles to health-care services, the report notes. A U.S. Government Accountability Office report in 2020 said one-way travel

time to health-care services increased approximately 20 miles from 2012 to

2018 in communities with rural hospital closures. Travel times for less common

services increased even more.

Recommendations: The report offers several short-term proposals to help shore up rural health systems, largely measures to stabilize payment models and extending Medicare sequestration requirements until two years after the federal public health emergency for Covid-19 ends.

The report also offers what it calls "evidence-based, viable solutions to the health care crisis in rural America" that seek to "stabilize rural health-care systems, strengthen the newly created Rural Emergency Hospital model, ensure an adequate workforce, and broaden access to virtual care in rural America."

No comments:

Post a Comment